Three Times Lucky: The Driftless Region

By Steve Swenson

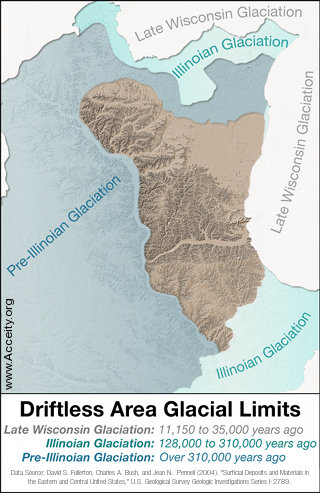

If and when the next glacier comes to Wisconsin, the smart bet is a move to the Driftless Region. While many are aware that the state’s Driftless Area escaped glaciation during the last glacial period ending 11,000 years ago, few appreciate that glaciers also missed this region twice before.

So if and when the next glacier comes, it surely will be cold in the Driftless, but you’re unlikely to find a glacier in your backyard.

What is the Driftless Region?

“Drift” is all the soil, sand, and rocks great and small, transported and deposited by glaciers. In places that glaciers failed to reach, there is no drift; hence the term, Driftless. What the Driftless Area does have is older topography, carved by flowing water for millions of years.

That is, while much of the rest of Wisconsin was flattened and filled in by glaciers, the Driftless Region held onto its deep river valleys.

This unique landscape covers most of southwestern Wisconsin, but also extends into southeast Minnesota, northeast Iowa, and a little bit of northwest Illinois.

The region’s physical diversity provides the perfect canvas for a wealth of biological diversity. A single landowner’s property can have a dry bluff prairie, a soggy floodplain forest, and other habitats in between – each with its own plant and animal communities. For nature-lovers, the Driftless has great allure.

Driftless Not Once, Not Twice, But Three Times

Beginning about 2.5 million years ago, the earth began experiencing periods of warmer and colder climate, the result of changes in the earth’s orbit and tilt. The cooler periods marked the formation and expansion of glaciers.

There were three distinct glacial periods: the Pre-Illinoian (2.5 million to 500,000 years ago), the Illinoian (300,000 to 130,000 years ago), and the Wisconsinan (31,500 – 7,000 years ago in WI), separated by distinct periods of warming and melting. Within each of these periods, glaciation was quite dynamic with numerous glacial advances and retreats.

During each of these glacial periods, the maximum extent of the glacier knocked on the door of the Driftless, but never went in.

Why is this? Imagine tipping a bucket of water over in a parking lot. The water travels toward the lowest spots on the surface, and so, too, do slow moving glaciers.

As each ice sheet expanded from the north, it flowed until it reached a low spot in central Wisconsin. But the slightly higher elevation of the Driftless Region forced the thin, leading edge of the ice sheet to travel uphill.

Eventually the sheet could no longer move upward and halted, leaving the Driftless Region beyond untouched. In addition, two other low elevation areas undermined a glacial takeover of the area. The basins of Lake Superior and Lake Michigan not only are low spots, but they also orient east-west and north-south, respectively. Neither orientation pointed the glaciers directly toward the Driftless, which lies to the southwest.

Now, before you start believing you have your glacier evacuation plan figured out, consider another issue. Although the Driftless was never overtaken by ice, it nevertheless was affected by the glaciers. During the glacial periods, the Driftless cooled to the point of resembling our northern tundra with a permanently frozen subsurface. So not only was it driftless, at times it was treeless.

Maybe a move south is more sensible when the next glacier comes.

For more information on the map, see Mapping the Driftless Area at www.acceity.org.