Prepare for Ticks with the Experts

By Denise Thornton

If you are going into a wooded area anywhere in Wisconsin, you need to be taking tick precautions. According to Rebecca Osborn, Vector-Borne Disease Epidemiologist at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, “We are seeing the number of tick-borne diseases increasing in Wisconsin, including Lyme disease and anaplasmosis (our second-most common tick-borne illness) as well as others.”

Even if you have never had Lyme disease, you probably know others who have. The numbers are sobering. “The CDC reports over 3,000 cases of Lyme disease a year in Wisconsin—but it might be 10 times higher than that,” says Mike Hillstom, a DNR forest health specialist. “There is a lot of underreporting. A lot of the symptoms are flu-like so going thru the pandemic the past couple of years, there is even more confusion about the cause of these symptoms.”

Osborn says, “Thankfully, most of the tick-borne diseases that occur in Wisconsin, including Lyme disease, can be effectively treated with Doxycycline a prescription antibiotic. The one exception is Babesiosis (a parasitic disease) that is carried by the same tick that spreads Lyme disease, but it is not a bacterium, so it has different treatment recommendations. We recommend testing for other diseases as well, if any tick-borne disease is suspected. They can mimic each other.”

Wisconsin is home to a number of different ticks, but it is the deer tick that can spread Lyme disease.

“We didn’t have our first confirmed report of a deer tick in Wisconsin until the late 1960s,” says P.J. Liesch, director of the UW Insect Diagnostic Lab. “Fast forward to today—they can be found in every corner of the state. This is not something our grandparents or their grandparents contended with. It is definitely an emerging health threat here in the state.”

Deer Tick Habit and Life Cycle

Ticks are most common in woods and the junctions between woods and meadows or lawns. Like many other tiny animals, ticks live with the daily risk of desiccation. If they lose too much moisture to the air around them, they will dry out and die. Liesch described a study by a UW researcher. “They climb up, start to dry out, go back to the ground level to wick up moisture, and then they can go back up to a more exposed location on a plant hoping to grab onto a host that they brush against. They have to keep making these trips all day.”

The deer tick is particularly susceptible to drying out, so they tend to stay in areas with a lot of leaf litter and vegetation where they can be protected from direct sunlight. Other tick species are more resilient. The wood tick (also very common in Wisconsin, but it doesn’t spread disease in our state) is more likely to be found in drier open fields and grassy areas.

Susan Paskewitz, UW-Madison Department Chair of Entomology and director of the Upper Midwestern Center of Excellence for Vector-Borne Disease, notes that “when we are out collecting ticks, a downed log seems to be a place we are likely to pick them up.”

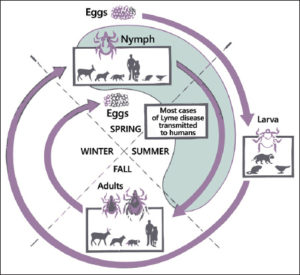

All ticks have complex life cycles, but it’s a good idea to become familiar with the deer tick’s life cycle and know its habits to determine where and when you are most at risk—although there really is no time of year when you are completely safe.

Ticks usually live two years in Wisconsin and go through a complex set of life stages as they grow. After a blood meal on a deer, the female tick lays 2-3,000 eggs in the spring through early summer, and then she dies.

The eggs take another month to hatch into larva. “We don’t see larva on people very often,” says Paskewitz. “Our skin might be too thick for them. They are very tiny.” August and September are peak larval activity. Larva seek out a blood meal from a bird or rodent that may be carrying Lyme disease. After they feed, they molt into nymphs who take a blood meal, then rest till the following spring. Late spring of their second year, nymphs take their second feeding. This is the most likely time to get Lyme disease.

“Nymphs are the most common stage for transmitting Lyme disease to people,” Paskewitz says. While 40 percent of adult ticks are infected and only 20 percent of nymphs—people are more successful at finding adult ticks on themselves because nymphs are the size of a poppy seed.

“When we are out in sandals in June and July is just when the nymphs are more active,” she added. “You can see in the epidemiological patterns what time of year most cases are diagnosed. It correlates with the nymphal peak.” Keep in mind there really is no time of year when you are completely safe.

In the fall, if nymphs can get a blood meal, they molt into an adult tick in the second and third week of October. Adults prefer to feed on large mammals, such as white-tailed deer or humans. The female finds a host for a blood meal, mates with an adult male tick, lays hundreds to thousands of eggs, and then dies.

According to the Minnesota Department of Health, some adults who do not feed or mate in the fall will survive through the winter and then come out to feed and/or mate the following spring. If there is little to no snow cover, and temperatures rise above freezing—it is possible to find an active adult tick searching for a host on a warm winter day!

Protection from Ticks

“Once nymphs or adult ticks are on the body, they quickly try to find a protected place to insert their mouth parts,” says Paskewitz. “They can be on the host for three to four days. Laboratory studies show that they don’t transmit the pathogen for 24-36 hours. That’s why it’s important to do a tick check every day. There is some data suggesting that they could transmit more quickly, so the bottom line is to get them off as soon as you can.” Recognizing that it is hard to find a tick on your own back, Paskewitz suggests using a scrub brush in the shower.

Even better, try to avoid getting ticks on your skin in the first place by following these recommendations:

- Light-colored clothing can help you spot ticks. Wear long pants and long-sleeved shirts. Tuck your pants into your socks.

- DEET insect repellent can help repel ticks to some degree. Paskewitz says a cloth treated with DEET and dragged along the ground will pick up ticks, but within three minutes, 80 to 90 percent of them have dropped off. Do a good spritzing of DEET on pants and socks. Ticks are most likely to be getting on your clothes from the waist down. The immature stages will be on low vegetation no more than a foot high.

- For more protection, the clothes you wear in the woods can be treated with the insecticide Permethrin. You can buy clothes pre-treated or spray a mixture on your own clothes and let them dry. This treatment is good for up to six washes.

No single method is 100 percent effective, so combining these recommendations is the best strategy for avoiding tick bites.

If you do find a tick embedded in your skin, check out this CDC website for advice on how best to remove it.

There’s an App for That

Much of the info in this article can be found on The Tick App a Project of our Midwest Center of Excellence for Vector-borne Diseases in a collaboration between the UW-Wisconsin and researchers in the northeast states, where Lyme disease is also a serious problem.

This app contains details on how to remove a tick, tick prevention, and general information. You can also use it as a daily log which assists scientists to learn more about ticks. “We researchers use it to understand more about human behavior—what people are doing and where and when they pick up ticks,” says Paskewitz. “This app provides a direct route to us experts. You can take a photo of the tick and send it to us, and we can answer questions like which tick it is, whether you should be watching for symptoms of disease over the next month and whether you should see your doctor to get preventive treatment.”

For a complete list of tick-borne diseases in Wisconsin check out this website.