Looking back at the History of Wisconsin’s Forests

“The history of Wisconsin’s forests includes what happened yesterday and 10,000 years ago. It’s all part of a continuum — both the natural and human aspects of our forests. They can’t be separated,” says Ed Forrester, president of the Forest History Association of Wisconsin (FHAW). FHAW is dedicated to the discovery, interpretation, and preservation of Wisconsin’s forest history.

“We also follow forest history going back nearly to the end of the last glaciation when most of Wisconsin was tundra. That period determined so much of what Wisconsin is today. Eventually, the story of our forests has become a human story. Archeology and forestry go hand in hand for us,” Forrester continued, referring to the 1,200-year-old dugout canoe discovered on the bottom of Lake Mendota in Madison last November and the more recent discovery this May of a 3,000-year-old canoe on the bottom of the same lake. “Those canoes, and others preserved in museums around the state, were the work of the first loggers,” says Forrester. “They converted a tree to a useful product.”

Another major influence on our forests during the time of human habitation is the beaver. “The demand for beaver pelts in Europe brought the French and Spanish and later English explorers to travel the rivers of Wisconsin, and trade with various Native American villages, where they saw the pine trees. That made the world aware of a valuable resource here.”

Not only were the trees here valuable as lumber, but as a crucial nutritional supplement. “In the 1600s scurvy, or lack of vitamin C, was a major problem for sailors,” says Forrester. “Why didn’t Wisconsin lumbermen suffer from it in the winter? French explorers were having trouble with scurvy on the St. Lawrence River and were helped by Native Americans who showed them that white cedar tea can prevent scurvy. I have to believe that occurred in Wisconsin as well.”

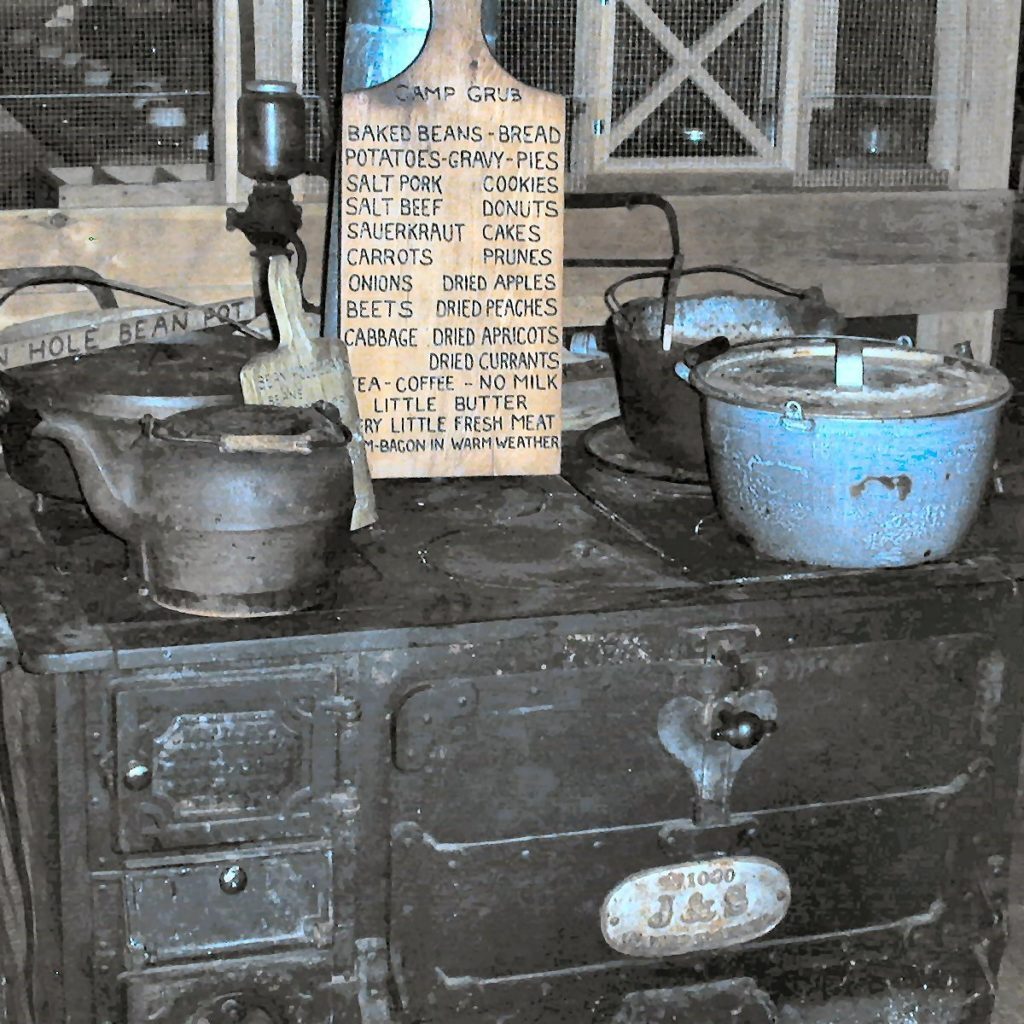

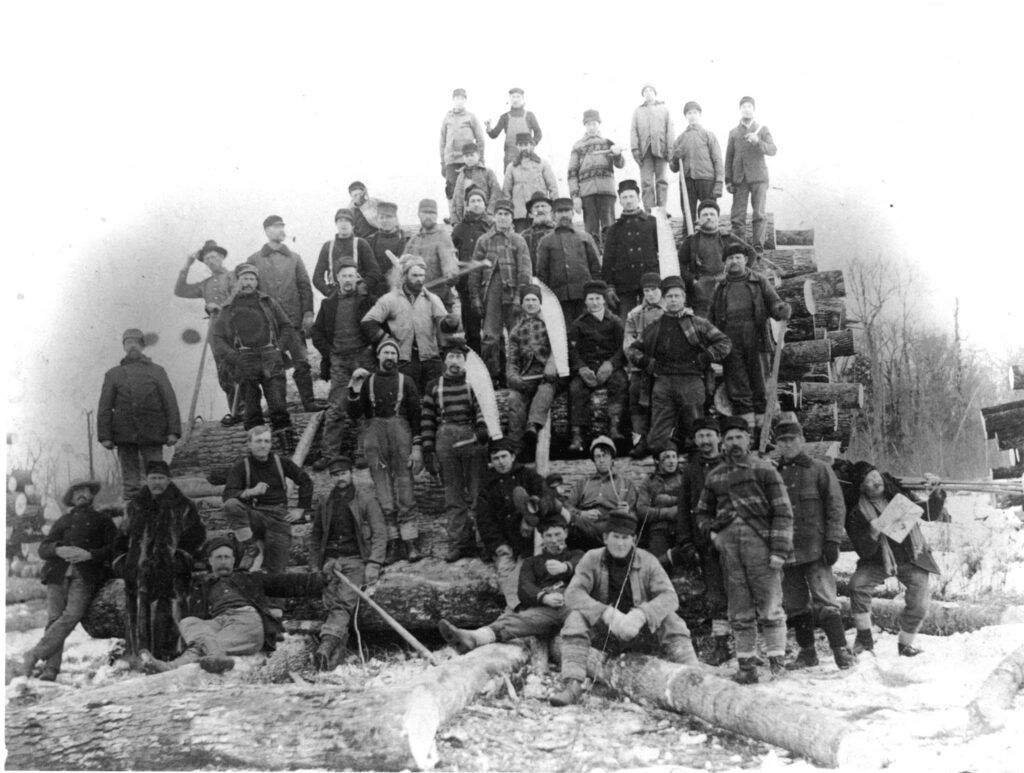

As European settlement in Wisconsin took hold, the logging of Wisconsin’s timber stands rapidly accelerated. According to the Wisconsin Historical Society, the 1890 U.S. census counted more than 23,000 men working in Wisconsin’s logging industry and another 32,000 at the sawmills that turned timber into boards. “Each winter, the lumberjacks occupied nearly 450 logging camps. In the spring, they drove their timber downstream to more than 1,000 mills. Logging and lumbering employed a quarter of all Wisconsinites working in the 1890s.”

“The largest lumber company in the world in the 1880s-90s was the Knapp, Stout Lumber Company in Wisconsin,” notes Forrester. “Early logging in Wisconsin focused on white pine, but after most of the white pine had been harvested, around 1900, the paper-making industry grew in Wisconsin. Jack pine was an excellent source of high-quality long fiber wood for making quality paper. Once most glossy magazines were produced on paper made from Wisconsin Jack Pine.”

Lumber camps have a rough reputation that was probably exaggerated. “ ‘Hayward, Hurly and Hell’ — that phrase was generated by the young laboring force hitting towns at the end of the lumbering season. But drunken and disorderly behavior was dangerous in the woods,” Forrester says. “Most lumber camps prohibited alcohol and many prohibited smoking. The saw mills did the same. An itinerant labor force of 16- to 25-year-olds, often first generation immigrants, were swinging the axes. They did not get paid until the wood was sold and paid for. They would work during winter and not get paid till the next fall. The camp bosses tended to be responsible family men in the area who had a team of horses.”

Until railroad track could be laid into the forest, logging was a winter activity, Forrester explains. “If you dropped a big log on the ground in the summer and dragged it through sand and mud, you got a lot of gritty foreign material in the wood that would quickly dull the saws. It was better to fell and drag logs to the river in the winter.”

The early logging that involved river log drives did not create much permanent settlement in northern Wisconsin, according to the website Wisconsin 101. Most early lumbering involved pine because softwoods could be floated down rivers from short-lived camps. The site notes, “In northeastern Wisconsin, three major river networks sent logs to either Green Bay (and then on to Milwaukee and Chicago), Oshkosh, or various mills along the Wisconsin River from Rhinelander to Wisconsin Rapids.” With the expansion of railroads in the 1880s, “northern Wisconsin opened new areas for the lumber industry, especially for hardwoods like maple, which could not be floated down rivers.”

Further, according to the Wisconsin 101 website, “Railroads led to the creation of more sawmills and the towns that supported them in the north woods. Most cities north of a line from Fond du Lac to La Crosse began as lumber towns connected to markets by the railway. Some thrived, and some would become ghost towns when the forests were depleted. Railroads continued to be the primary method of transporting logs until the 1930s, when improved roads allowed trucking to surpass rail.”

Fires were a constant threat throughout early European settlement, often triggered by settlers, lumber camps and railroad trains. The Peshtigo Fire in October 1871 was the most devastating U.S. fire of its time. Though the Chicago Fire, which burned at the same time, killed 300 people, 1,200 people were lost in Wisconsin along with two billion trees as a result of the Peshtigo Fire.

Improved lumber technology and increasing demand for lumber, as well as uncontrolled fire, resulted in dramatic changes to Wisconsin’s forests. According to Timber! The History of Forestry in Wisconsin (UW-Stevens Point), “In the late 1700s, virgin forests covered about 30 million acres (86%) of Wisconsin. White pine was nearly wiped out in Wisconsin by 1920. Between harvesting, clearing land for farming and wildfires by 1915 only 380,000 acres (1%) of timberland remained. By the 1920s — with so much land that could not support forestry or farming — a group of foresters, working with the Legislature, lumber and logging associations, and conservation groups began to reestablish Wisconsin’s forest. “Today Wisconsin’s forests total over 16 million acres (46% of the state) and foresters are managing our forests with sustainability in mind.”

The changing forest uses are based on the human stories — of loggers, immigrant farmers, village shop keepers. “The stories of human competition in its finest and worst points are woven into this story,” says Forrester, “and our organization is working to make sure that what happened in the past, as well as current events, are documented and digitized, and made available to the public. Our goal is to serve as a resource to all the state historical societies and anyone else who is interested.” Their materials are archived at the University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point campus.

FHAW offers webinars about 10 time a year, which can be found on their website. They publish a quarterly magazine and a monthly electronic newsletter. “We welcome new members statewide,” says Forrester. The membership fee is $20 annually. To join, write to Forest History of Wisconsin, Box 186, Bangor WI 54614.

By Denise Thornton

All photos complementary of Forest History Association of Wisconsin.