A Green Investment: The Story of Our Land and Eco-Home

As a monthly contributing author to My Wisconsin Woods, I love sharing the stories of Wisconsin landowners. This issue I’ll be sharing the journey that my husband, Doug Hansmann, and I have been traveling as landowners of 44 acres near Dodgeville.

By Denise Thornton

Our story begins with a bike ride we took out into the Driftless Area on our first date, and though our jobs drew us away to the Netherlands, then Indiana, the northern Chicago suburbs, and back to Madison, we always felt the pull of the Driftless.

Doug has credentials in conservation biology and environmental chemistry, and mine are in science writing. From that first bike ride, we shared a dream of becoming stewards of a parcel of land. We wanted an ecologically interesting property, and one that offered a south-facing building site for a solar-efficient home.

The land we found rose up the east side of a winding valley. We first walked it on Labor Day weekend 2004. After several years of searching, my heart was pounding from the topographical nuance of a protected hollow where a ravine crossed the valley under a bowl of blue sky. The previous family had farmed it for generations, planting where they could, and leaving the steepest slopes to mixed hardwoods. In the late 90’s, they planted most of the fields with alternating rows of evergreens and oaks, enrolling 22 acres in CRP. A stand of conifers planted earlier already stretched 20 feet high, but mostly, we inherited acres of saplings hidden in fields thickly over grown with thistles, wild parsnip, and other invasives. We borrowed a brush mower and began to free up the rows of young trees.

Eventually we got our own brush mower, but our favorite tool has long been the ageless and agile scythe. Larry Cooper, a blacksmith living nearby at the time, urged us to try one, and our collection has grown to four snaths (the wooden handles) and 5 blades. Every summer, we walk our small prairie, other open areas, and trail edges scanning for the usual undesirable suspects that perpetually pop up. You can take out a clump of too-aggressive golden rod with a swing of the blade, or slip the tip of the scythe around the stalk of a wild parsnip crowding a prized compass plant, and take it out with a flick of the wrist. (Well, it usually takes a second round in a few weeks to really completely discourage it.) In the process, you get to walk every inch of the area in a productive monitoring session. (Larry Cooper is also the source of our favorite gardening tool, the broad fork.)

Though the building site was the driving issue during our land hunt, we did not build on our land for 10 years. One of the first advisors we sought out on how to manage a piece of land for wildlife told us bluntly, “Don’t build on it.” We still planned to build, but realized we had a lot of research to do on how to build with the minimal possible footprint. Also, our oldest daughter, Della Hansmann, had recently started architecture school, and we decided to wait until she was ready to “practice” on her parents’ new home.

So, for years, we contented ourselves with taking time after work to make the 40-minute drive out to our land and spent many late afternoons and long summer evenings keeping our young trees happy — though for most of the alternating rows of oaks, it was too late. They were repeatedly browsed to the ground by deer.

While walking our land during our first year with Kristin Westad, an expert in prairie ecology, she observed that a field recently planted to pine and spruce was also sprouting vestiges of the long-gone prairie. We were thrilled to invite prairie back to that sunny ridge but learned that reimbursing years of CRP payments that the previous owners had received would add serious cost to the project. We compromised by selecting a few acres that seemed to have the richest remnant prairie plants and started to clear them as soon as the CRP paperwork was signed. Most of those pine and spruce were about my own height, and I took on the task of cutting each one down with a bow saw, piling them on a tarp/sled and dragging them down to the bottom of our new prairie, where Doug and I would burn them on weekends.

In the meantime, while following the farm lane up through the woods to work in our prairie, we discovered hoary puccoon, wood betony, and a clump of yellow lady slipper in a quarter-acre clearing. I started to scythe out anything encroaching on them, and they flourished. When we realized that the farm lane was passing right through our finest patch of puccoon, we moved the lane. Kristen identified other native plants struggling in the shade, and with the help of a Prairie Enthusiast grant, a team with chainsaws widened the lane into a glade, which we have been gradually expanding as time and energy allow.

We burn our prairie and glade, as well as an area surrounding our yard that we call Birdland. We collect, buy, and sow seed to expand the variety and acreage. Our work in the woods includes gradually clearing out trees crowding the oaks to create more of a savanna and suppressing forest floor invasives (first and foremost honeysuckle and multiflora rose) where we can.

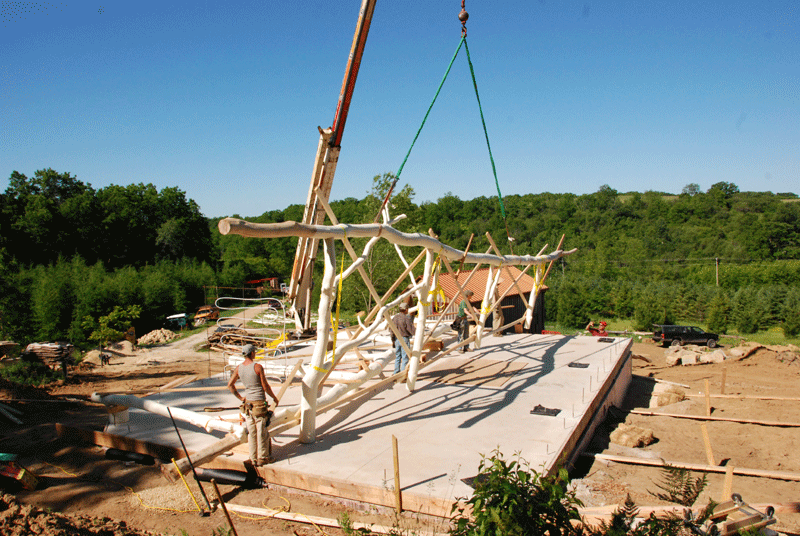

When Della earned her master’s degree in architecture, she went to work for WholeTrees Architecture, a company based at that time in La Crosse. Its founder, Roald Gundersen, who had recently been featured in Natural Home Magazine, was building some of the greenest and most novel homes we had ever seen. He worked on the principal that many woodlands are crowded with trees that are not straight enough for the lumber industry, but could be crafted into unmilled, branching, timber frame structures, thus improving the health of the woods and creating new homes with local materials.

In 2012, as soon as Della had enough experience to take the lead on a project, we started to build Underhill House. I have written extensively about the process on my blog, Digging in the Driftless, and we held regular open houses throughout the project. Our house is both a home and a laboratory or sustainable shelter ideas incorporates straw bale insulation, passive solar design, in-floor heating warmed from a solar hot water panel array, lime plaster exterior wall surfaces, PV solar electric panels, and last but not least, a sod roof. WholeTrees no longer builds homes likes ours, but many of the design and building elements they employed have worked well for us and could be applied to more conventional structures.

During our first Underhill winter, a polar vortex dropped temperatures below minus 30. The sun rose that morning in a cloudless sky, and we were eager to put our place to the test. We turned off the propane boiler. By 10 a.m., the solar hot-water panels were pumping the heat to the floors, that was accumulating in our 166-gallon basement storage tank. As well, the sun was pouring in through our south facing windows further warming our thermal mass concrete floor. We ate lunch in T-shirts.

Summers are also comfortable, partially thanks to our deep eaves and sod roof. Think of walking barefoot across an asphalt drive on a sunny day and then stepping into the lawn, where that heat energy is being photosynthetically transmuted into growing plants.

Operating the greenest shelter we could build, and stewarding our prairies and woodlands takes all the energy and hours we can give to it, but as Robin Wall Kimmerer says in Braiding Sweetgrass, “Action on behalf of life transforms. Because the relationship between self and the world is reciprocal, it is not a question of first getting enlightened or saved and then acting. As we work to heal the earth, the earth heals us.”

Ideas to Try at Home

While most homes do not enjoy the insulation value and carefully aligned and designed structure that Underhill House does, there are practices anyone can employ to improve their passive solar potential.

— Consider improving your home’s micro-climate. Think of where you could use another tree to shade you from blistering summer heat.

—Choose energy-efficient window coverings, and use them to keep out both winter cold and summer heat. It can really make a difference.

—Use natural ventilation to your advantage instead of automatically reaching for the thermostat. Our house was designed to employ stacked ventilation. In our case, cool air enters from our lower-level, shaded, west windows and exits through the loft windows on the east. Many existing houses can set up stacked ventilation with a little thought.

—Doug and I have a lot of fun and get good ideas about how to manage our indoor temperature with our trigger-operated infrared thermometer. You can aim it at any surface and read the temperature. We like to see how various aspects of our house are performing to learn where tweaks might add comfort.