The Benefits of Forest Bathing and Therapy

What is forest bathing? Breathe deeply, slow down, and immerse yourself in the natural beauty of Wisconsin’s forests. Forest bathing offers a calming escape and a mindful way to reconnect with the outdoors—no hiking boots required.

by Denise Thornton

When I first heard the term “forest therapist” I was both intrigued and a bit skeptical. What could a forest therapist teach me? My husband, Doug, and I have been stewarding 44 acres in The Driftless since we fell in love with them in 2003. Working on our land always leaves me feeling good, if also exhausted. Is that the therapy a woods can offer? Doug and I have read scores of articles and books, and taken courses on many aspects of land management. But there is always something more to learn, so I reached out to Martha York, a certified forest therapy guide.

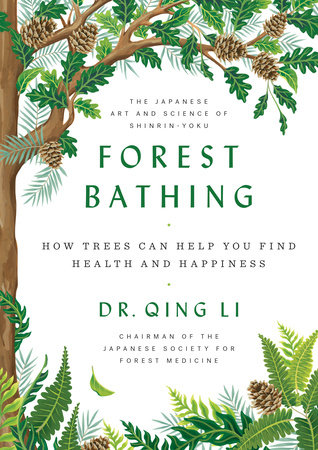

York is a licensed clinical social worker with her own practice. “I was raised by trees,” she told me. “I grew up on a Christmas tree farm, and when I heard about forest therapy, I had to learn more.” The practice of forest therapy developed in the 1980s when Japan was dealing with increasing urban stress. They developed Shinrin-yoku, which translates roughly as forest bathing, or forest immersion. Dr. Qing Li, has studied the effect of forest environments on human health and is author of Forest Bathing: How Trees Can Help You Find Health and Happiness. Among other benefits, Li noted that trees produce essential oils that are part of a tree’s defense against disease and insects that appear to boost the human immune system. (See sidebar Forest Bathing and Health.)

Forest immersion can offer other benefits as well, said York, who was trained by Amos Clifford, founder of the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy Guides and Programs, and author of Your Guide to Forest Bathing. “I went out to Colorado in 2019 for an eight-day immersion experience, and it changed my perspective on who I am and how humans fit into nature,” she said.

York and I met at Festge Park near Cross Plains on one of this year’s first gorgeous, blue-sky May mornings. Before we began, she offered me a folding pad, which proved very useful.

“This practice isn’t about exercise or identifying plants,” York explained. “It’s a different way of experiencing. We move slowly, and we don’t talk a lot. We’ll keep our phones off and focus on being present. I will give you invitations as we go along.”

We paused at the trail head to tune into the space with York’s invitation to consider those who have passed this way before us, both indigenous and animal. At her suggestion, I closed my eyes and imagined my feet rooting to the earth and contemplating how abuzz with life the ground below me was. “The trees are connected under the earth,” she said. “We can choose to connect with the living world instead of the human world and experience the stability of being on the earth. Wendell Berry wrote, ‘What I stand for is what I stand on,’ and that reminds us of our place here in nature.”

Then York suggested I tune more deeply in to my other senses, and slowly turn in a circle noticing what drew my awareness. “If you find a direction that particularly calls your attention — just luxuriate in it a bit and notice what is there for you.” She added, “When you are ready to open your eyes, you might imagine that you have never seen this scene before. What is it like to really see it for the first time.”

I was already realizing that this approach was nothing like the way I normally enter my wooded trails. Usually, instead of a kneeling pad, I have a tool in hand, and I’m striding out briskly, scanning for issues like encroaching invasives, and contemplating their treatment — adding to my ever-growing to-do list.

Instead, York suggested that we spend the next 10 minutes or so wandering on our own in a heightened awareness of the motion around us. Time slowed as I watched the last year’s dead stalks, along side the fresh, tender greenery — each responding in its own way to the whisper of breeze. My knee pad got plenty of use as I studied tiny bees gorging on dandelion pollen, and ants following their mysterious but purposeful pathways. I sat still for a moment, enveloped in a gentle waft of warm, spring air. My eye was caught by an aspen, still rooted, but at an arching 45 degree angle to the ground. As I tuned in to its unhurried, but inevitable downward motion, I could feel my breath relaxing and my heartbeat slowing.

The next invitation was to look for aspects of wabi-sabi, another Japanese concept which involves finding beauty in things that are impermanent and imperfect, as they respond to the forces of nature. I found myself absorbed in the wabi-sabi-ness of the trees around me. Any tree that has been holding its ground for decades has taken on some injury that is slowly working its impact. For a change, I was looking at a tree leaning against its neighbor without my thoughts rushing to — how are we going to get that tree down safely?

Our forest therapy wrapped up with a simple tea ceremony. York assembled 3 cups, a thermos of dandelion tea, and a plate of fruit on a bench. I happened to have a bag of walnuts and dried cherries which added to our feast. “We always pour the first tea for the earth,” she said. “Much gratitude to the land and this beautiful Driftless Area.”

Articles on forest bathing often include suggestions of places to practice located anywhere from the Sequoia National Park, to the Ohboa Forest two hours outside Kyoto, Japan, to Costa Rica’s Monteverde Cloud Forest. I’m sure those are inspiring locales. But what could be more inspiring for landowners in Wisconsin than their own woodland? Taking inspiration from my walk with York, I have found myself eagerly following my own trails with fresh eyes, as I take some time to soak in my surroundings and enjoy an exhilarating combination of calmness and energy. Though my forestry maintenance may have been temporarily postponed by pausing to reintroduce myself to my woodland, I return to it with increased enthusiasm.

INVITATIONS

Here are some of the many Invitations a forest therapist uses that you can jot down and take along with you.

Motion: Everything is in motion: the clouds, the air, and everything living in your woods. Sometimes you need to look closely to see it.

Wabi-Sabi: Find the beauty in decline and decay.

Treasure: Imagine there is a treasure out there for you. It could be an inner or outer treasure. It is yours to find.

Play: Notice how nature plays, and invites you to play.

What Draws You: As you wander, linger with whatever you are being drawn to. Sit a while and notice the slow reveal.

HEALTH BENEFITS

In his research, Dr. Qing Li has found that forest bathing has many benefits to human health.

- Reduced blood pressure

- Reduced stress

- Improved mood

- Increased ability to focus, even in children with ADHD

- Accelerated recovery from surgery or illness

- Increased energy level

- Improved sleep

- Boosted immune system functioning, with an increase in the count of the body’s Natural Killer (NK) cells.

FIVE SENSES

Dr. Qing Li, who studied environmental medicine and was part of a team at the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan in 2004 suggests how to use our senses during forest immersion.

- The sense of sight: Forest landscape- green, yellow, red, and other colors

- The sense of smell: Especially good smells, like the fragrance from trees

- The sense of hearing: forest sounds, birdsong

- The sense of touch: Touching trees can put your whole body in the realm of the forest

- The sense of taste: Eating foods and fruits from forests, or ‘tasting’ the fresh forest air

FURTHER READING

Forest Bathing: How Trees Can Help You Find Health and Happiness By Dr. Qing Li

Wabi Sabi: Japanese Wisdom for a Perfectly Imperfect Life By Beth Kempton

Healing Trees: A pocket Guide to Forest Bathing By Ben Page

The Nature Embedded Mind: How the Way We Think Can Heal our Planet and Ourselves By Julie Brams