Seasonal Changes in Your Woods this Fall

Curious what changes you may see in your woods this fall? Learn about fall phenology from Dr. Stan Temple, a Senior Fellow and Science Advisor to the Aldo Leopold Foundation.

By Denise Thornton

Gardeners, landowners, and nature lovers have always practiced phenology, marking when the first robin appears each spring, or when the acorns start to drop on your roof come fall. Taking these observations more seriously, and keeping regular tabs on what happens where you live can be a fascinating hobby, and a valuable tool in caring for your woods.

Phenology ties the traditional calendar of days, weeks, and months to nature’s ever-changing timetable. And though fall and winter observations may lack the stirring first sightings in spring, when we are inspired to chart the migratory birds arriving, and first blooms of our favorite flowers, these later months are a very good time to tune into the phenological charm of what is happening in your woods .

“Everyone is aware that the physical environment is changing rapidly in the fall,” says Stan Temple, a Senior Fellow and Science Advisor to the Aldo Leopold Foundation. Temple writes and updates the Aldo Leopold Foundation’s annual Phenology Calendar. “We are just past the fall equinox. Days are getting shorter, and temperatures are falling,” says Temple. “These are two of the important drivers of the phenological events taking place in this season.”

Oaks in October

Enjoying fall colors overshadows other phenological events in autumn, but there are less noticeable changes happening. We all see that oaks are dropping their acorns, but there is a subtle difference between white and red oaks that happens in October just after their acorns have fallen.

“White oak acorns germinate in October and send down a root, then pause their development over the winter,” says Temple. “Red oak acorns don’t germinate until spring.” Why do white oak acorns germinate as winter approaches? “The hypothesis is that they do it in response to passenger pigeons.”

In times past, 4-5 billion passenger pigeons were a force to be reckoned with. They nested in colonies that covered hundreds of square miles — sometimes crowding up to a hundred nests in a single tree. “Now extinct, these birds were incredibly efficient predators on acorns. White oaks developed what many ecologists think was a defensive mechanism to have their acorns germinate very quickly before they could be eaten by nesting passenger pigeons the following spring,” Temple says. “When passenger pigeons were around, white oaks were the dominant oak species in midwestern forests. Red oaks have become dominant now that their acorns are no longer being gobbled up by passenger pigeons.”

October Flowers

“If you have witch-hazel shrubs in the understory of your woods, you will be treated to one of the last blooming events of the year,” says Temple. The unusual yellow, fragrant flowers bloom from October to December when overstory leaves have fallen. The flower petals open on warmer sunny days and curl up when the temperature drops. In addition to the yellow flowers the leaves turn vivid yellow, orange, and red.

As temperatures drop, critical thermal thresholds are reached. The first frost generally occurs in October, but Temple notes a more subtle transition takes place for many animals when the average temperature drops below about 50 degrees. “Their physiological systems and behavior start to change when this threshold is passed — especially for cold-blooded animals,” he says.

Insects

You have probably seen orange and black woolly bear caterpillars crossing your path. “This time of year, they are urgently looking for winter quarters under tree bark or litter before the average temperature drops below 50 degrees,” says Temple. “They are about to enter diapause, a state of suspended animation, where their development into an Isabella tiger moth gets arrested until spring. To survive winter temperatures they produce a chemical that protects their tissues against damage from freezing and thawing.”

“A rich folk lore has developed around them, but it is not based on fact. The story goes that if you see a wooly bear heading south, it’s going to be a hard winter. But they are just looking for shelter in what ever direction they can find it. Another tale is that the severity of the winter can be predicted by the width of their stripes, but that width is determined by how many of their successive molts they have been through. So stripe width indicates how old they are, and not future weather severity.”

Another autumn observance is that insect sounds come to an end. “People notice that crickets chirp more slowly as the weather gets colder, allowing you to tell the temperature by their rate of chirping,” Temple says. “This bit of folk knowledge has a factual basis. The relationship between temperature and how rapidly crickets are chirping is named Dolbear’s Law because Amos Dolbear figured out that if you count the number of chirps in 15 seconds and add 40 — that will be very close to the exact temperature. One chirp per second would be 55 degrees. When the average temperature drops below 50, the chirps cease.” Mark that date in your phenological calendar!

Amphibians and Reptiles

In October, amphibians and reptiles start to go into brumation (hibernation is specific to warm-blooded animals). Many woodland owners in Wisconsin are host to gray tree frogs and are familiar with their musical calls through the summer. “When they stop calling, they are coming down out of the trees and looking for winter quarters in which to brumate,” says Temple. “They are seeking downed, rotten logs and deep leaf litter where they can get under protective cover. It’s important that your woods provide suitable places for them to winter as well as breeding ponds.”

It is also usual in October to notice snakes, especially common garter snakes, crossing roads and sometimes getting into garages or basements, Temple says. “They are also looking for a place to brumate, called a hibernaculum. They need a place deep enough to stay below the frost line and maintain a stable temperature. Hibernacula are often found in underground burrows, rock piles, dead trees, logs, and even man-made structures like building foundations or old wells.

Snakes live for multiple years, and the hibernaculum they use for their first winter will be the place they try to return to every winter for the rest of their lives.” Consider yourself lucky if you already have a snake hibernaculum on your property where snakes can successfully spend the winter. You could even consider creating a snake hibernaculum.

Birds

“Most people are aware that many of the birds that breed during summer in Wisconsin have left by October,” says Temple, “but those who have a feeder or who are out in their woods are also aware that a different group of birds are coming from the north to spend the winter here. They are collectively referred to as the winter finches: dark-eyed juncos, white-throated sparrows, purple finches, redpoles, pine siskins, and occasionally, the rare evening grosbeaks or pine grosbeaks. If your woods provide cover and food (or you maintain bird feeders) these visitors are likely to be in our woods all winter.”

The northern saw-whet owl is another bird that may be passing through, or spending the winter here. “Saw-whet owls are tiny and nocturnal, so they are usually overlooked,” Temple notes. “But if you want to have fun in your woods in October, load up your phone with recorded calls of the saw-whet owls. If you go out at night and play their calls, you are likely to find out if you have saw-whet owls in your woods because they will respond and call back at you. Bird banders this time of year will stay up all night with their nets trapping and banding saw-whet owls as they migrate through Wisconsin. On a good night — they might catch a dozen or more of them.”

Another October activity in the bird world is the “Fall Shuffle” — a traumatic period in the life of certain young birds, says Temple. “They have been kicked out of their parents’ territories and are wandering around trying to find a place to settle. In the process, they trespass on other birds’ territories and are being rebuffed.”

There are two species of shuffling birds landowners might detect in their Wisconsin woods. “There is a brief period during the fall,” says Temple, “especially in October, when adult male ruffed grouse are drumming, which is more commonly heard during their mating ritual in the spring.” In fall they are drumming to ward off young grouse that might try to settle on their territory. Young owls also take part in a fall shuffle. “During October you may hear a lot of hooting, as adult barred owls defend their territories from younger owls that are shuffling around looking a home of their own.

Mammals

One very conspicuous mammalian activity in October woods is white-tailed deer beginning to rut. “Bucks rub their antlers on saplings and make scrapes on the ground, and this indicates that the breeding season is about to begin,” says Temple.

In October many small mammals are going into torpor or hibernation. “Chipmunks that have been active in the woods are going to enter a state of torpor in October and will be in that state for the rest of the winter,” says Temple. “Torpor is different than hibernation in that they regularly wake themselves up to eat food they have stored in their den.” So, if you have been watching chipmunks scurry around collecting nuts and seeds, mark your calendar when they seem to disappear.

Some mammals, such as groundhogs, are truly going to hibernate and enter an extended deep winter torpor. Some smaller animals like woodland jumping mice will also hibernate, but many mouse species like deer mice and meadow voles remain active all year long.

What You Can Do

There are things you can do on your land to increase survival rates of overwintering animals. “How you manage your woods often determines whether animals looking for places to spend the winter will find shelter. They are looking for special situations where they can best survive the coming winter.” says Temple.

“All these events that we record on our phenological calendar are shifting with climate change,” Temple adds. “Autumn events are happening later and later as fall temperatures are getting steadily warmer. While in spring, annual events are happening earlier. That means Wisconsin winters are getting shorter with many consequences for plants and animals”

“There are online citizen-science projects that allow observers to upload their seasonal observations to data bases that scientists use to analyze phenology, among other things,” Temple says. “If you are paying attention and recording what you observe, it’s a good idea to share your observations with others. It’s so easy. You can do it from any of your devices.”

Citizen science programs depend on volunteer observers to share their findings, which allows scientists to track changes and understand the trends which can inform management practices, for our own property and more regionally.

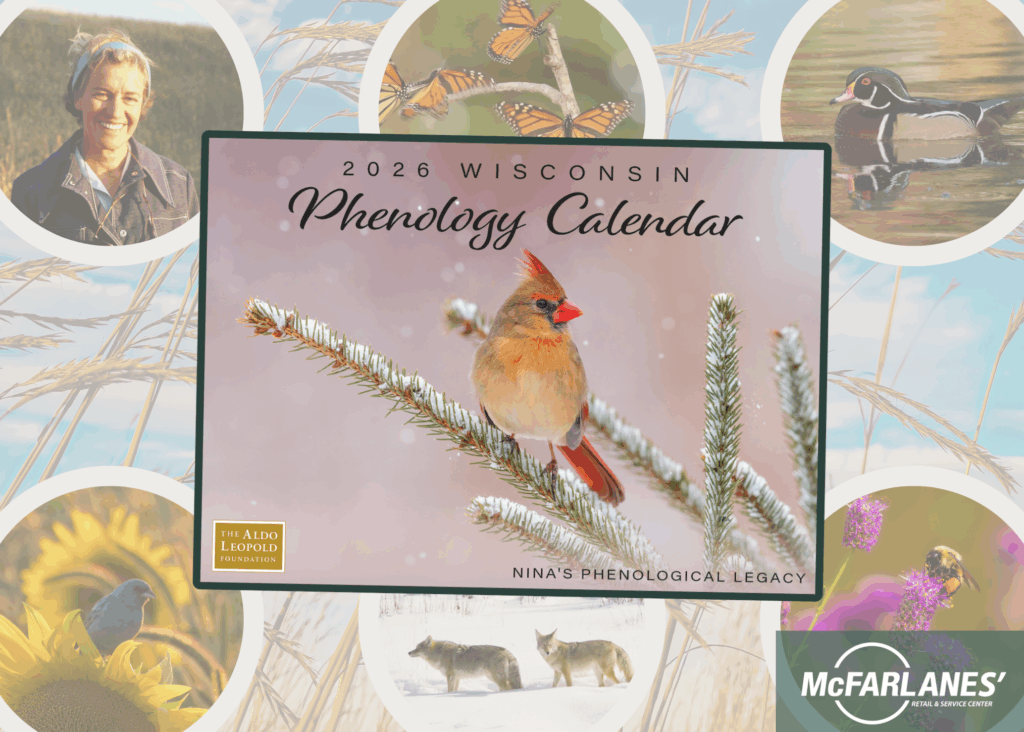

2026 Phenology Calendar

Ready to start recognizing phenological patterns on your property? Check out the Aldo Leopold Foundation’s 2026 Phenology Calendar. Whether you’re a seasoned pro or new to the practice, phenology is a fantastic way to immerse yourself in the natural world! These calendars also make a wonderful holiday gift for the nature lover in your life. Purchase yours here.

Where to Look for Participating Organizations

The National Phenology Network is a good starting point. It is a monitoring and research initiative focused on collecting, organizing and delivering phenological data to support natural resource management. With this app, you can track the status of spring migrations, see forecasts of pests and invasive species, and track changes in plants and animals. You can share your findings as you track your own timing of plant and animal activities through the seasons here.

iNaturalist is a world-wide citizen science project that is moderated by experts, and used for scientific research. Learn how to start participating here.

If birds are your passion, eBird is a good way to share your sightings and contribute to hundreds of conservation decisions, student projects, and valuable research. Learn how to get started here.