Ticks in ’25

It's summertime in Wisconsin, and that means it is prime time for ticks. Read this article to learn more about the state of ticks and tick disease in 2025.

By Denise Thornton

Many of the hazards that Wisconsin landowners face were familiar to their grandparents, but not tick-borne diseases. A Milwaukee dermatologist reported the first U.S. case of Lyme disease’s bulls-eye rash in 1970. Today tick-borne disease has been reported in almost every county of the state, and tick bite-associated emergency department visits statewide are increasing every year.

On average, about 4,000 cases of Lyme Disease were reported in Wisconsin each year from 2018 to 2022. In 2023, 6,379 cases were reported. The main drivers in the tick population increase we are experiencing are the regeneration of forests since their decimation by logging in the early 1900s, and the rebounding deer population.

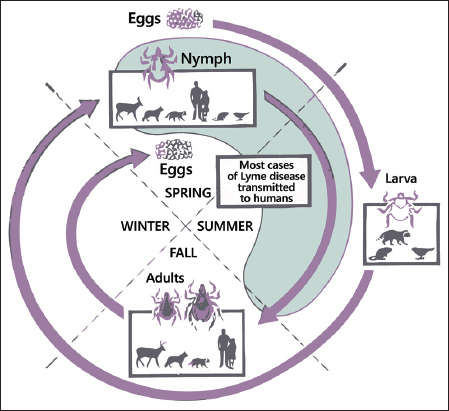

Find more information on the deer tick’s habits and complex life cycle and also protection strategies in a previously published My Wisconsin Woods’ article Prepare for Ticks with the Experts.

“This is the time of year when ticks are always abundant,” says Susan Paskewitz, a medical entomologist at UW-Madison. Nymph-stage ticks are present during June and the first few weeks of July, and though nymphs are only the size of poppy seeds — smaller than 1/16” — they can transmit disease.

PROTECT YOURSELF

Paskewitz is one of the developers of The Tick App, which can be used to report ticks and is a quick source of information about them. This app was recently mentioned in a NYTimes article, How Bad Are Ticks This Year? Paskewitz says findings by her colleagues show that tick numbers are about normal in Wisconsin this year. However, she notes that a past study shows that both mice and deer are drawn to places where there are lots of acorns during mast years. “This gives you two of the important mammalian pieces of the picture. The deer can drop off adult ticks, and mice are really good hosts for tick larva (as are chipmunks). When these rodent populations do really well, they feed more tick larva, and that will mean more nymphs the following year.” Tick larvae pick up Lyme Disease and other pathogens in that first blood meal from rodents and then transmit those pathogens — perhaps to an unprotected person — when they have their next blood meals as nymphs and again as adults.

“It’s really important for people to protect themselves when they are outside,” says Lyric Bartholomay, a medical entomologist at UW Madison in the School of Veterinary Medicine. “We recommend light-colored clothing that you have treated with permethrin. Ticks can get on you from your feet up. So do everything you can to protect yourself from that initial contact. We often wear rubber boots — there is nothing they can grab onto on a rubber boot. If you are wearing other foot wear, spray it with DEET.” It is also a good, neighborly idea to keep some extra socks treated with permethrin around for guests to wear and tuck into their pants when they are walking your trails.

Bartholomay suggests walking in the middle of trails. “Especially if the trail gets some sunlight, stay away from the edges. Ticks can dry out in the sunlight, so they are going to stay in the more shady, brushy edge areas.”

“Unlike DEET (which is only a repellent) permethrin has both insecticidal properties and repellent properties,” says P. J. Liesch, director of the UW-Madison Insect Diagnostic Lab. “It can stun or irritate ticks, and they may fall off, but if they maintain contact long enough, it can kill them outright. The label will indicate if the application will last through multiple washings. There are also brands of clothing that are impregnated with permethrin. This technology was developed by the U.S. Military for soldiers deployed to spots with harmful insects so that they didn’t need to lug gallons of insect repellent with them.”

Make sure you are using an EPA-registered repellent that has science backing it up. The EPA has a repellent finder tool to help you select the right product for you. “Make sure to read all the label instructions, which will tell you where you can apply it — to bare skin or only to clothing. The label will tell you how long it will last, and how often you should re-apply,” Liesch adds.

YOU HAVE AT LEAST 24 HOURS

It is important to get out of the clothes you wear in tick country as soon as possible. And it’s a good idea to toss those clothes into a hot dryer to dehydrate any ticks that may be lurking. Shower with a wash cloth and wipe all of your skin, in order to wash ticks down the drain before they have a chance to get their mouth parts into you.

“I have had ticks on me, and they can attach pretty quickly,” says Paskewitz. “It could be only 10 to 15 minutes till they start to feed. The key issue is to get the tick off within that first 24 hours after it has attached. During that time, they are going through a slow process as their bodies change to expand and accommodate all the incoming blood. Imagine your body doubling in weight in two days — your skin would take a beating. At first they feed slowly. Intake starts to ramp up by the second or third day. That’s when the spirochetes, a type of bacteria, have made it into their salivary glands, and you are more likely to get disease transmission.” Note: for anaplasmosis, transmission takes about one day, and for babesiosis (both tick-bornee diseases), transmission can take a day and a half.

TICKS CAN INVADE YOUR YARD

Staying out of the woods may not be enough protection for those who live on the edge of a wooded area. Paskewitz is involved in a study of about 80 houses in the Eau Claire area and a similar study in the Baraboo area where there is a grassy interface between the house and the woods. “We found the vast majority of homes had ticks in their lawn, and some had a really amazing number.”

Paskewitz and her team have found that application of pesticides reduced the tick numbers 85 to 90 percent. “You can hire professionals or do it yourself with an over-the-counter material you can get at the hardware store,” she says.

“Deltamethrin is used by professional exterminators. Triazacide is available to homeowners.

This year we are having homeowners around Mirror Lake see if they can treat their lawns themselves,” says Paskewitz. “Not everyone wants to use pesticides. We are not suggesting using it on the entire grassy lawn, but it is something you can apply right at the edge of the woods and make a barrier to stop ticks. It worked for weeks, and we got robust reductions. Triazacide is granular. You water it in, and once it has dried, it is thought to be safe, including for pets.”

PROTECT YOUR PETS

It is important to protect pets that may be exposed to ticks. Check with your vet. Liesch has received many reports of ticks found on dogs in the winter. “People say they don’t need tick treatment in December and January, yet if we have a mild winter, your pets could encounter ticks or fleas. If there is a day with no snow on the ground and temperatures in the mid 40s — you can’t let your guard down. Ticks could be active.”

Unfortunately, there is not yet a tick collar for humans, and all three experts emphasized the importance of tick checks for anyone who has been in tick country. Paskewitz has been conducting a study using mannequins dressed in different colored clothing with actual ticks glued to them to learn if test subjects could identify where ticks are. “We discovered that people are good at finding ticks on a white background, but below the waist, it is much harder to identify ticks — even on white pants and shoes,” she says. “It makes sense to have someone else help you search, and to use a tool like a flashlight. Perhaps use your phone to get pictures of parts of the body less accessible to a visual inspection.”

Protective clothing, repellents, tick checks, and showering are all useful. But the best strategy is to employ all four.

NEW TICK TO WATCH OUT FOR

As if ongoing concern over existing ticks isn’t bad enough, the Asian Longhorned tick was found for the first time in the U.S, 2017. “It’s a super invasive species that arrived in the New Jersey area and spread quickly in the northeastern states,” says Bartholomay. “It’s a nasty one because the females can make clones of themselves, and they can turn up en masse. These ticks are light, reddish tan and about the size of a wood tick — larger than 1/8”. If someone sees a tick they haven’t seen before, please alert The Wisconsin Department of Health Services tick identification,” says Bartholomay.

“It only takes one Asian Longhorned tick in a new area to start a new population there,” says Liesch. “They like livestock, and a concern is that while each individual tick isn’t taking that much blood, hundreds may impact an animal’s health due to blood loss. This newly-concerning species has recently been detected in Michigan.”