The Wisconsin Lumber Prognosis

Wisconsin landowners aren’t imagining it — selling timber has become noticeably more challenging in recent years. From shifting housing trends to competition with synthetic products, today’s lumber market is shaped by a complex mix of pressures. This article breaks down the major forces influencing timber demand and what they mean for woodland owners.

By Denise Thornton

If you think lumber sales are not what they used to be, you are not alone. Many Wisconsin landowners find themselves looking at their many rows of softwoods and their woodlots overcrowded with hardwoods, and yet they cannot find a lumber company willing to buy and harvest their timber. What is driving — or suppressing — Wisconsin’s lumber market these days?

HOUSING MARKET

The main factor influencing lumber demand and pricing is the housing market. “When the housing market is booming, you have more demand for lumber and engineered products like plywood and oriented strand board (OSB), (a type of engineered wood formed by adding adhesives and then compressing layers of wood strands that make it suitable for load-bearing applications),” says Scott Lyon, WDNR Forest Products Team Leader-Applied Forestry Bureau. Softwood species are used in housing construction, and hardwoods, which primarily dominate in Wisconsin, are used for applications like cabinets, flooring and furniture.

“Right now, our housing market nationally has dropped significantly, from one million to below 900,000 units from July to August of this year,” Lyon says, based on recent National Association of Home Builders and Wisconsin Builders Association housing data. “Multifamily units have dropped nationally from 400,000 to 300,000 in the same time.

While Wisconsin had 6,960 housing permits from January to June this year — a half percent increase from last year, Lyon notes, this may be a fluke. “When homes went up in price, interest rates also went up in price, and some people can take that on, but others who have a lower mortgage interest rate on their current home are reluctant to move to a bigger house and pay not only a higher price, but also a higher interest rate.”

A few years ago during covid when saw mills were shut down, lumber prices were higher due to a shortage of materials. Also the demand rose because people were sitting at home and deciding to remodel, according to Lyon.

“The price has gone up five percent for kiln dried lumber, Lyon notes. “Hard maple and red oak have been trending up over the past half year. White oak and walnut have been stable for the past few years.”

With softwood, it depends on what you have. “Some pine species — red pine in general — have become easier to market” says Troy DeLaet, Wood Production Manager at Nekoosa Mill. “In its highest value form, red pine can be used as a utility pole or it can qualify as SPF (this category includes spruce, pine, and fir commonly used for framing and general construction, if it has the right strength-to-weight ratio).

“The 2x4s that you buy at the lumber yard — most of them are red pine,” says DeLaet.

“White pine doesn’t have the strength to be used for dimensional lumber for construction.”

SUBSTITUTE PRODUCTS

Another factor that is lowering demand for Wisconsin’s timber is competition with substitute products. In every building project, wood has competitors. “We are all consumers,” says Lyon. “Our trends of what we want are always changing. In the 80s and 90s, our kitchens and floors were often red oak. Now the trend is to paint many of these surfaces. When I visited China even their airports had a lot of American wood, while our airports are all steel and plastic.”

“Substitution is a real challenge to the demand for Wisconsin forest products,” says Larry Krueger of Krueger Lumber Company, a buyer of standing timber, timberland, and cut logs.

“So many products that were once made of wood are now being substituted with synthetics that look like wood, such as vinyl flooring made from an unhealthy petroleum product,” Krueger says. “Kitchen cabinets are made of synthetic products painted gray or white instead of beautiful hardwood. That’s bad for our industry.”

LOCATION & TIMING

Where your trees grow, and when they can be cut will make a difference in whether you can market them easily, according to DeLaet.

“It used to be easier to sell lumber regardless of where it was in the state due to greater demand throughout the state. Now proximity to the markets is a huge deal. Sales are easier in the northeast part of the state than they are in the northwest or the far south.”

Seasonal restrictions can hamper sales as well. “Winter-only cuts make that window of harvest smaller and more challenging to sell. I would put in a plug for not making unnecessary time restrictions,” DeLaet notes. “If someone says I don’t want you in the fall because I deer hunt, and you can’t cut in summer because of oak wilt, I understand, but you have reduced your marketability. I cut my own land in the fall while bow hunting, and the deer are in the woods all the time eating the tops.”

“The loggers can be more selective on what they buy now, and they are focusing on high volume and quality, compared to timber they may have bought six years ago. If landowners are struggling due to the size of their timber sale, consider grouping sales with your neighbors to make it more attractive to a logger,” DeLaet suggests.

PULP WOOD DEMAND

Current conditions make for a mixed demand for pulp wood. “Wisconsin has a lot of specialty paper and container manufacturers,” says Lyon. “During covid, everyone was buying online goods that were delivered in cardboard containers, and that brought the demand for pulp up.”

“Some companies are switching to paper-based containers for single-use packaging, such as fast-food chains, and those containers may have been made here in Wisconsin. We also make some specialty paper items like dental bibs and gowns. But wood pulp is now competing with recycled fiber in addition to imported pulp such as Eucalyptus from Brazil,” he added.

“I don’t see a prospect for change in the demand for pulp wood at this time that would increase marketability for timber sales,” says DeLaet.

TRANSPORTATION

Lumber companies face challenges getting wood from the forest to their facilities, and they are also challenged getting the finished lumber product to customers. “Globally, it’s more difficult to compete,” says Lyon. “Some of our surrounding states have better access to rail lines.”

For Wisconsin lumber products that must be shipped long distance, that means packing it in shipping containers. “There is only one place in Wisconsin to put our shipping containers onto railroad cars — Chippewa Falls,” says Krueger. “We used to have places in Stevens Point, Neenah, Green Bay and Milwaukee. They are all gone. Now we have to truck shipping containers from Chicago, fill them and truck them back to Chicago where they can be transported by rail.” Krueger attributes this change in rail service over the past 22 years to precision railroading. It is more profitable for the railways to ship large numbers of rail cars all at once from one major metropolitan area to another. “When we have to pay more for transportation,” he says, “landowners get less money for their trees.”

TARIFFS

“Looking back to 2008 when the domestic housing market crashed, if it wasn’t for export, we would have lost a lot more lumber companies in Wisconsin than we did,” says Lyon. “That period opened a lot of new markets for our wood in areas like China and Vietnam. Our local markets are valuable, but Wisconsin lumber now competes globally — from hardwood, and softwood to paper and packaging.” That means current tariffs are affecting our lumber sales.

“Wisconsin produces more agricultural products than we can consume here in the U.S., so we always have to export some of our lumber,” agrees Krueger. “Unfortunately, there are a lot of tariffs going up and going down and pausing and starting at the moment, on the things our country imports, and our customers overseas are responding with tariffs on our exported products. This makes it difficult, if not impossible, to sell our products. That difficulty reaches all the way back to affect Wisconsin’s timber growers. but these are challenges that are fixable.”

FUTURE MARKETS FOR WOOD

Lyon says that the WDNR, along with other organizations, are working to develop more markets for Wisconsin lumber.

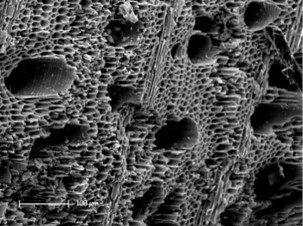

Cross-laminated timber (CLT) would be a great potential use for Wisconsin timber. The WDNR helped host a symposium in Milwaukee this September for architects, engineers, and others interested in innovative wood applications. CLT is a structural wood product made by bonding small pieces of lumber together to form panels and beams that can be used in large, commercial buildings. “At present, the closest manufacturer is in Illinois,” says Lyon. “Unfortunately, they are using a lot of southern pine because it can be more cheaply transported up by available rail, however they are willing to use more wood grown here in Wisconsin if the customer requests it.”

The WDNR recently coordinated a study with Michigan State University with the goal of locating mass timber industry to Wisconsin and Michigan. This could revitalize rural communities and enhance regional resilience in the forest products industry. “That is a hopeful future opportunity to help our lumber industry and our landowners,” says Lyon. Currently, WDNR is working with Michigan Tech University and the US Forest Service’s Forest Products Laboratory to have white pine lumber tested for use in cross-laminated timber. This could potentially open new opportunities for use for a species that is currently lacking in adequate markets in Wisconsin and the Great Lakes region.

Biochar is also being studied in Wisconsin as a use for biomass from forest management practices, urban tree and pruning activities, and sawmill residues. Biochar is charcoal used as a soil amendment for gardens and farmland. Biochar can be created in a “flame cap” kiln that limits oxygen.

“Small woodland owners can make biochar and use it on their own property on a small scale,” says Lyon. “There may be potential for a large-scale operation to be established in Wisconsin to assist with forest management for woodland owners and to support urban areas with substantial tree-removal needs.”

State government is getting involved. The Council of Forestry, Great Lakes Timber Professionals Association, and the Wisconsin Paper Council are putting together a road map for the industry. “Governor Evers provided a million dollars to advance this project,” says Lyon. “It will explore ways to expand our current timber industry and attract other industry here.”

Also, landowners may create a small market for timber through WDNR classes in local-use dimension lumber grading. This allows participants to mill and sell their lumber locally for one- and two-family residential construction.

Planting trees and managing forests is a commitment to our future. These ongoing efforts to develop and diversify our state’s timber industry are part of the process, and worth watching.